A new film launched by Historic England reveals more hidden stories behind artefacts discovered on the 18th-century Dutch East India Company (VOC) ship, the Rooswijk.

It features Icon member Angela Middleton, Senior Archaeological Conservator at Historic England, and showcases how the artefacts recovered, including 100 intricately etched sabre blades featuring faces of the sun and moon, have been investigated by specialists at Historic England’s Research Facility in Portsmouth.

The film also highlights various techniques that can help scientists to analyse finds like these.

About the Rooswijk

The Rooswijk was a Dutch East India Company vessel that sank on the treacherous Goodwin Sands in 1740. The ship departed from Texel in the Netherlands and hit a fierce storm on its way to Batavia (modern-day Jakarta), causing it to sink. The ship sank with all 237 members of its crew, trade goods, and personal belongings.

These new discoveries are the result of two excavations, carried out between 2017 and 2018 in partnership with the Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands to recover artefacts from the Rooswijk, which is currently at risk due to its position on the Goodwin Sands, off the Kent coast.

The Rooswijk became a Protected Wreck in 2007.

More than 2500 artefacts were recovered from the Rooswijk. Through a variety of scientific techniques, Historic England’s specialists have now recovered and conserved an array of artefacts, including etched sabre blades, carved knife handles, silver coins, thimbles, a nit comb and more.

This project is funded and led by the Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands in close collaboration with project partner Historic England and contractor MSDS Marine.

Icon member Angela Middleton, Senior Archaeological Conservator at Historic England, said:

It has been fascinating to slowly reveal the many secrets hidden for hundreds of years within the objects found at the Rooswijk wreck site.

We are delighted to share this new video about the artefacts and to highlight the incredible work that has been carried out by our specialists to preserve these items for future generations to enjoy.

Artefacts recovered from the Rooswijk

Sabre blades

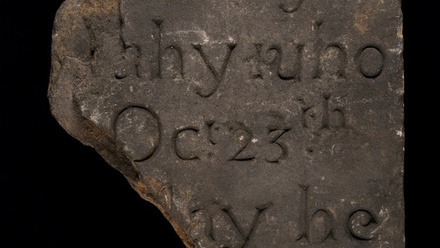

Chests containing trade goods, such as sabre blades, were recovered from the Rooswijk but were covered in thick layers of seabed concretion. A concretion is a material that builds up under the sea made up of shells, stones and other nearby artefacts. Specialists meticulously removed these layers using several different techniques, including a tool known as the ‘Air Scribe’, which eliminates small layers of concretion from around the blades.

All the blades were etched on both sides, with some displaying a sun, moon, stars, and a weaving snake.

The etchings were created with acid, as this was a cheaper alternative to engraving.

The designs etched onto the blades were not related to the Dutch East India Company but are like those seen on other bladed weapons across Europe, Africa, and the Middle East.

Martijn Manders, Coordinator Maritime Heritage Overseas and Rooswijk Project Lead at the Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands said:

The Rooswijk wreck lies at approximately 25 metres of depth in a highly dynamic environment. It takes a lot of effort to excavate a shipwreck under these conditions.

The conservation, however, has proven to be just as challenging. The conservators have done an amazing job.

Through mini excavations in the lab, we now know so much more about the ship, the people on board and their trade. I am happy the objects and the exciting stories they behold are now ready to be shown to the world.

Silver coins

X-radiography has been used to see inside concreted marine artefacts. This technique, which involves taking images of the inside of an object, has revealed silver coins, knife blades, and tool handles that have been hidden away since 1740.

The total number of silver coins recovered from the Rooswijk is 1846.

These coins can be divided into two categories: official and private. The official coins were company owned and primarily used for trade and exchange. The private coins were likely owned by crew members who intended to make a profit for themselves on voyages.

Smuggling silver coins was officially prohibited by the Dutch East India Company, but it seems to have been common practice by many on the Rooswijk.

It is possible that up to half the silver onboard the Rooswijk was illegal.

Many of the coins did not originate from the Netherlands; those being officially transported bear the letter ‘M’, meaning they were made at the Mexico City Mint.

Duncan Wilson, Chief Executive at Historic England added:

Historic wrecks contain a wealth of information that can inform about our maritime past but can be at risk of erosion. It is important that we document and research, where possible, the maritime heritage that historic wrecks reveal.

That way we will not lose the stories tied up in these amazing artefacts.