Introduction

In September 2021, the Franciscan Provincial Archives in Malta, received funding from the Barakat Trust to help with the conservation work required to make its collection of Islamic manuscripts accessible to scholars. Many of the Islamic manuscripts that form part of this project contain gospels and psalms in Arabic. These manuscripts are significant because Franciscan Friars studied them in Malta to learn Arabic before serving as missionaries in the Levant.

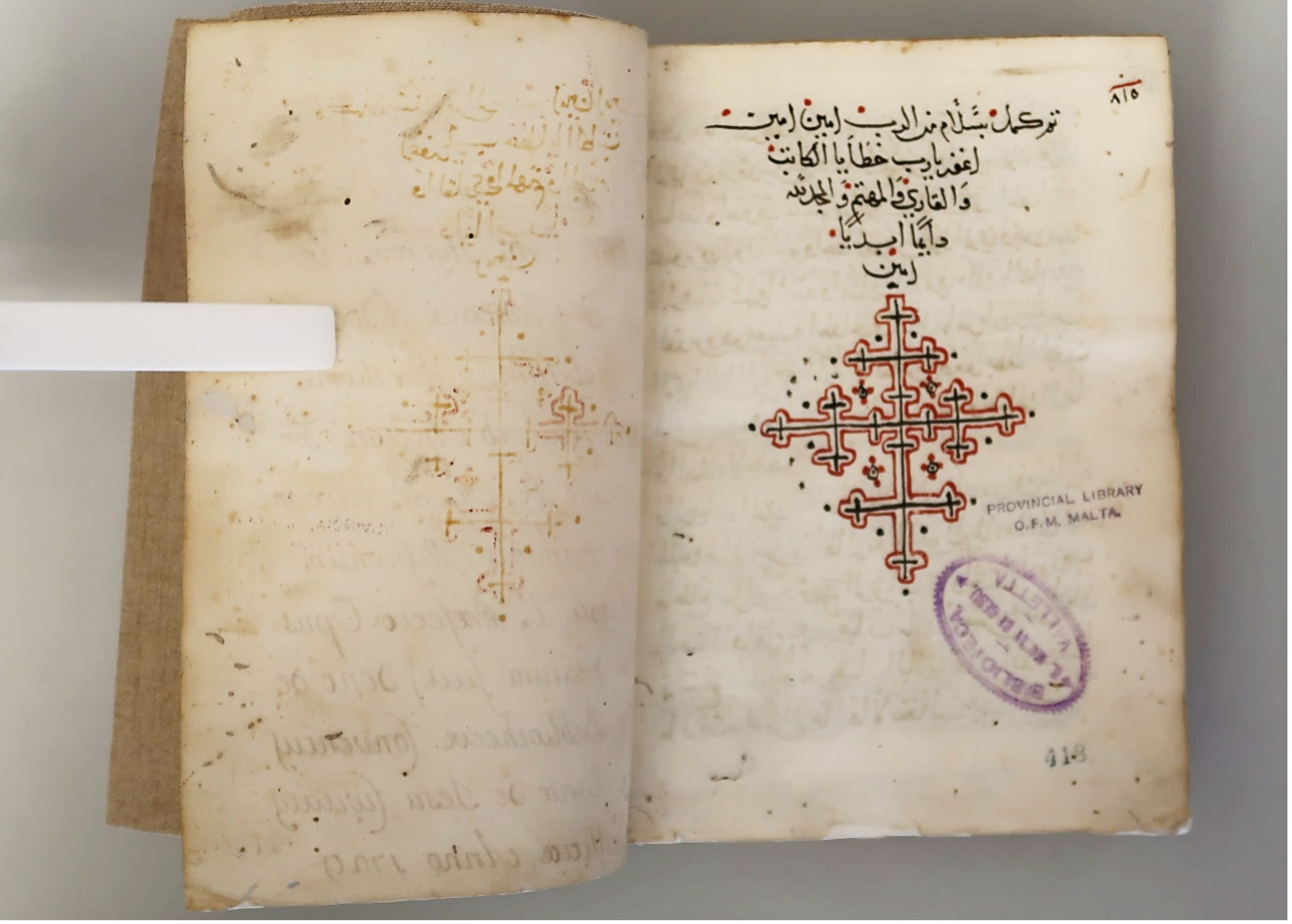

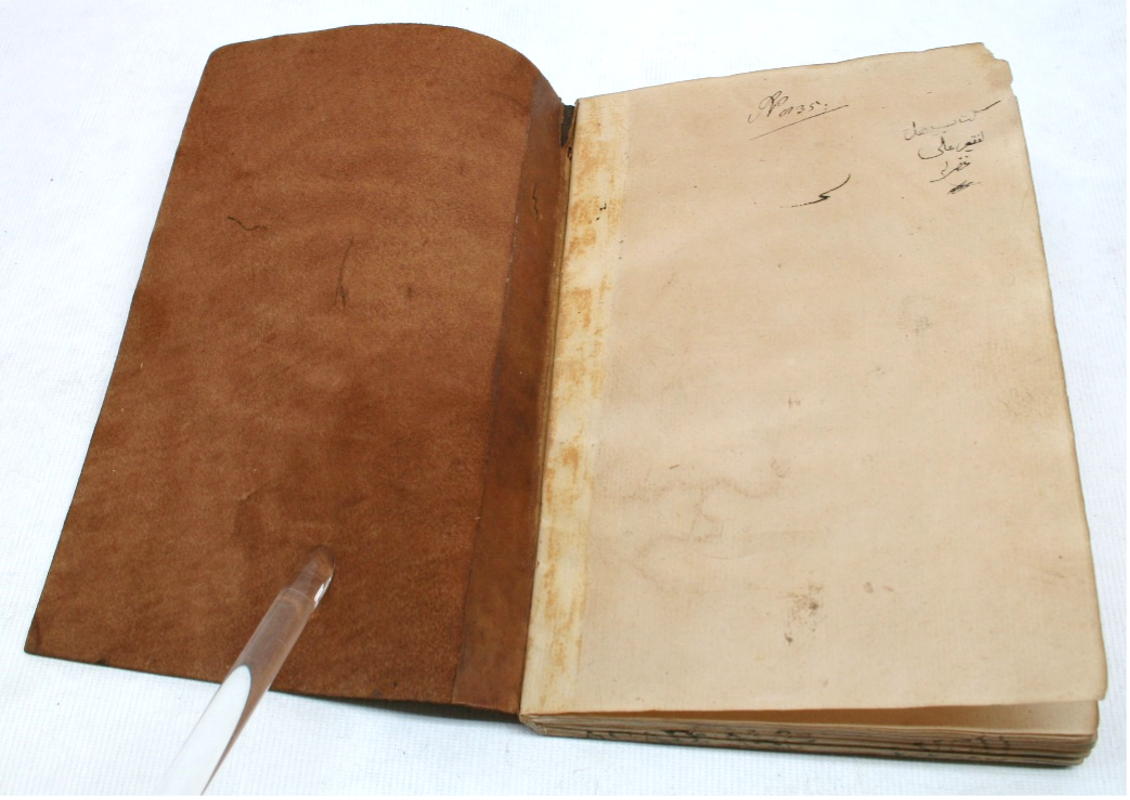

This project spans over a period of two and a half years and will include treatment on 33 manuscripts. I work on this project with two other conservators, Chanelle Briffa and Maria Borg, and in my blog, I describe how I treated four manuscripts last year. In Part 1 of the blog, only the work on the binding structure will be discussed. The four manuscripts under consideration were produced in 18th century Ottoman Syria (Fig. 1). These manuscripts contain a copy of Friar Arcangelo Zammit's Arabic translation of Francesco Mazzara's Leggendario Francescano. Scholar and Arabic instructor Friar Arcangelo Zammit died in Cairo in 1715 after 40 years of missionary work in Ottoman Syria.

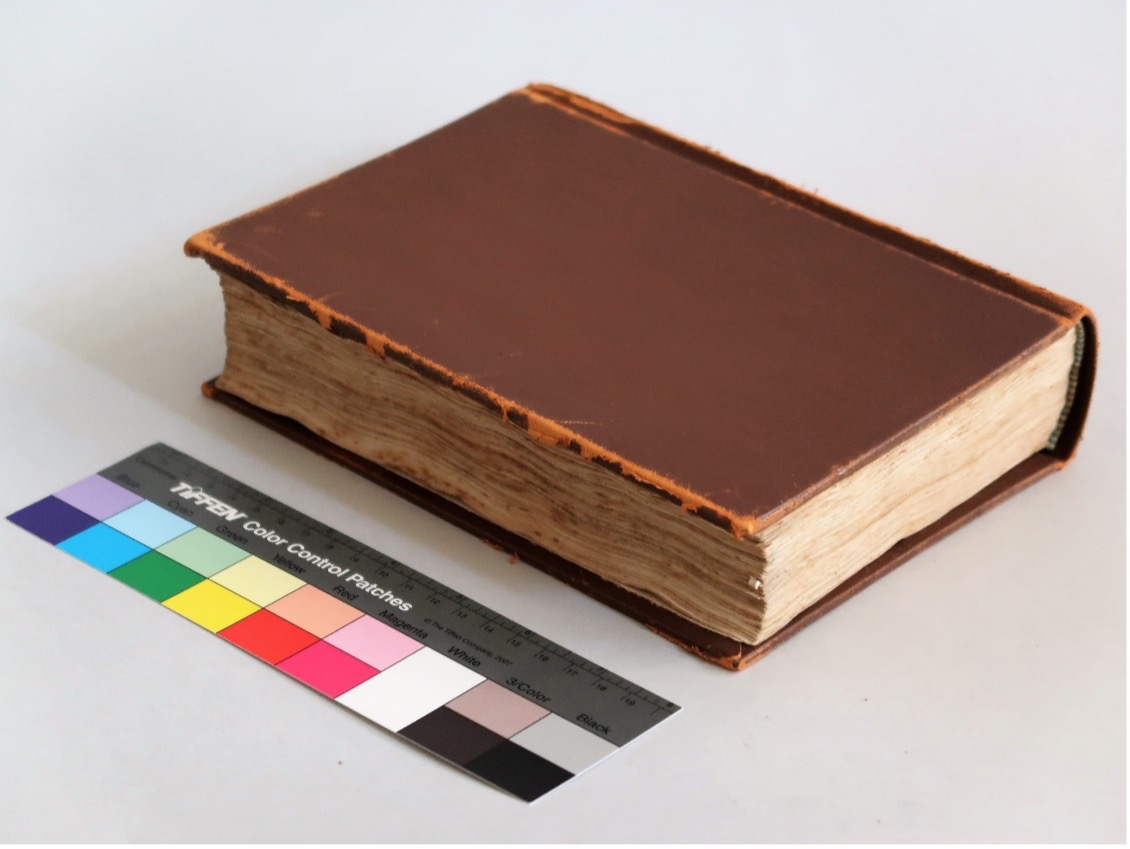

The manuscripts were in poor condition, and the rebinding in a 20th century Western manner was not sympathetic to the original Islamic materials (Fig. 2).

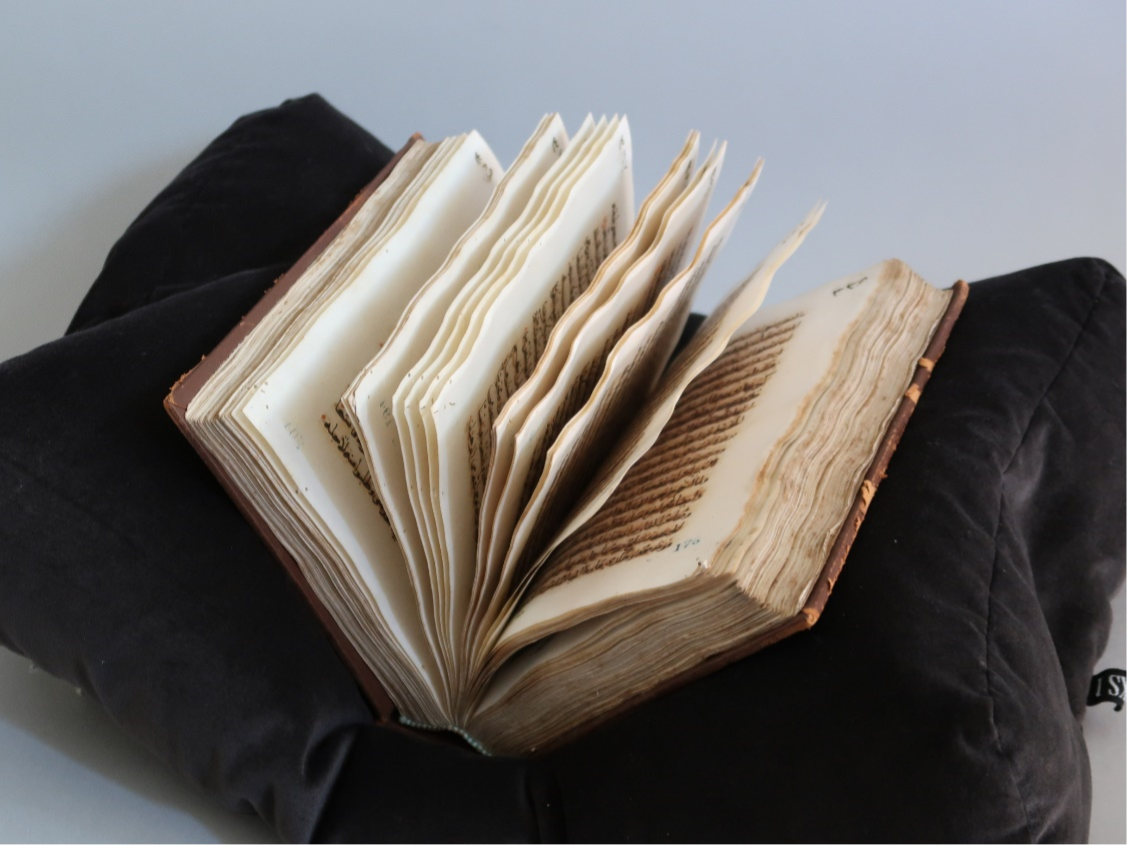

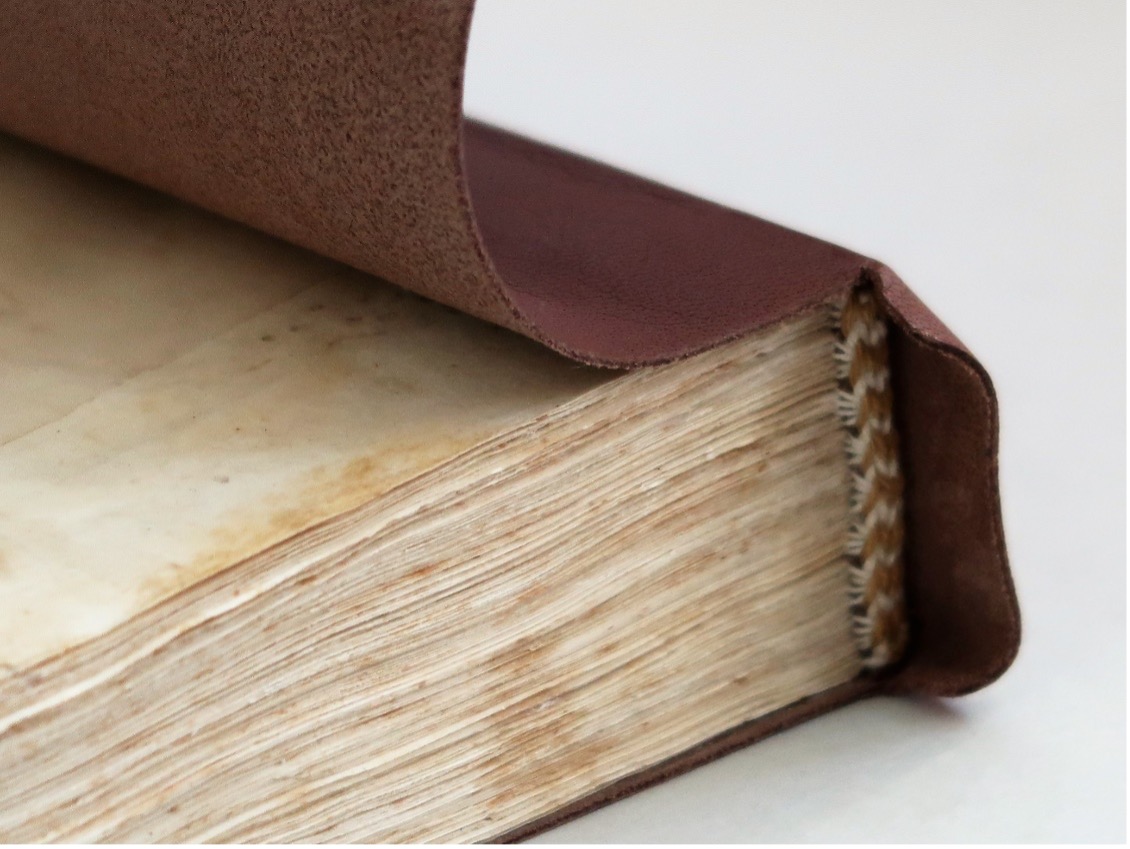

The introduction of the hollow tube, for the spine, for example, had a significant effect on the functioning of Islamic manuscripts and introduced new structural tensions. Similarly, the Western paper and thick synthetic adhesive on the spines of these textblocks prohibited the binding from functioning properly and made reader access difficult (Fig. 3).

The new binding

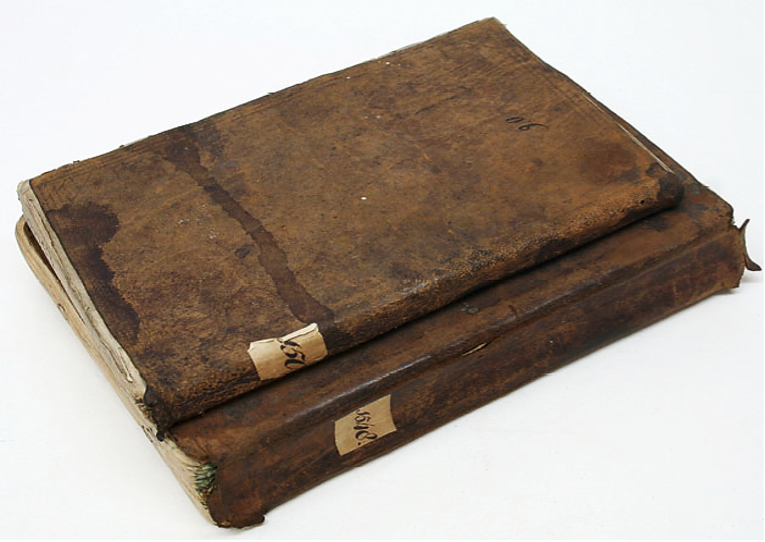

As previously stated, the Western binding structure presented significant structural issues and was not compatible with the original textblock. It was decided to rebind the four textblocks using more sympathetic materials. The design of the new binding was influenced by research I conducted on several Islamic limp leather bindings at the Leiden University Library, The Netherlands (Fig. 4).

We do not know the rationale behind the design of the limp leather binding, but Dr. Karin Scheper, Head of Book Conservation at Leiden University, believes that Islamic bookbinders may have provided it to customers as a less expensive alternative to manuscripts with boards. If tight budgets and limited resources require careful resource allocation in collections, the limp leather binding can also be seen as a less expensive option to rebinding Islamic manuscripts because they do not require boards. Additionally, they don't require conservators to spend a lot of time paring leather, which is advantageous in terms of time management.

A summary of the procedures that were carried out is given in the section that follows: first step was to remove the Western binding and clean the spine of all lining material. Next, the gatherings were sewn with unsupported sewing using the original sewing stations.

Following this, the spine was lined with light weight Japanese paper followed by a leather spine lining. The leather spine lining was attached to the textblock using adhesive. Next, the primary endbands are sewn through the spine lining.

The textblock is stabilised by this sewing, and the spine lining protects the gatherings from being torn by tiedowns as the manuscript is opened and closed. A thin leather core was used for the endbands so as not to obstruct the opening of the manuscript.

The secondary endbands were woven through the threads that were produced by the primary endbands. The secondary endbands are often sewn with two contrasting colours of thread. In this case, though, there was no evidence of the original threads. To avoid suggesting the presence of anything more specific in the past, subdued, and neutral colours were deliberately chosen (Fig. 6).

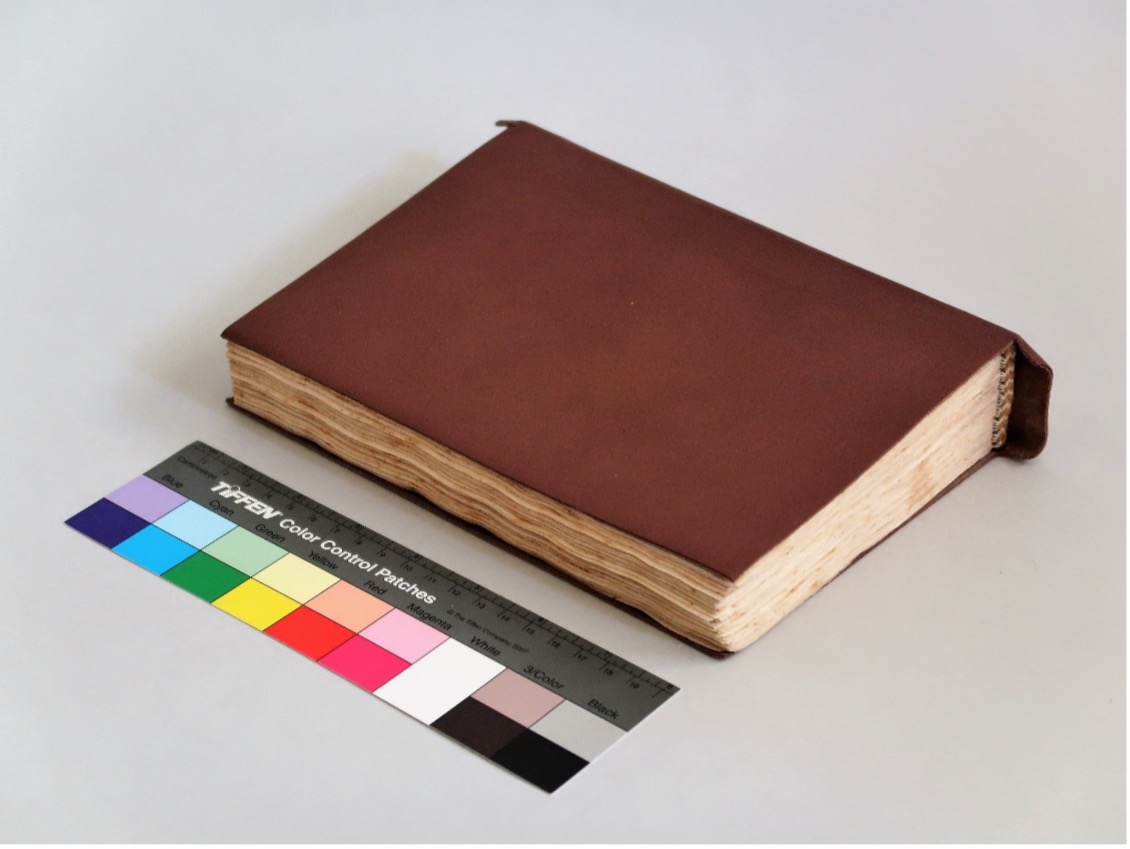

The covering material was then adhered directly to the spine lining, unlike the Western repair that had a hollow tube spine. A thick skin of goat’s leather was used since thick leather coverings may be seen on several historical limp bindings (Fig. 7).

Finally, the spine linings' pared flanges were attached to the cover's interior (Fig. 8).

Concluding thoughts

The compatibility of Islamic and Western bookbinding techniques has historically received little attention. Using Western binding methods to preserve Islamic bindings may be seen as diminishing the artefact. For that reason, conservation treatments of Islamic bindings should seek to preserve the traditional structure to maintain the authenticity of the object as far as possible.

Although my research on limp leather bindings is still ongoing, it has allowed me to extend one’s knowledge in a specific area. It would be useful to make comparisons with other limp leather bindings, in different collections to ascertain the extent to which this binding technique was used. I am currently working on adapting Mamluk cloth doublures to strengthen the limp leather cover attachment. This will be covered in the second instalment of my blog, which I expect to post soon. Finally, if anyone has similar experiences or different suggestions for how they would have handled the treatment, I would be very interested in hearing from you @davidplummer_.

Acknowledgments

This project is generously funded by the Barakat Trust and supported by Friar Noel Muscat, the Head Archivist of the Franciscan Provincial Archives. Thank you to Dr. Karin Scheper and Paul Hepworth for sharing their expertise on limp leather and Mamluk bindings. I also want to express my gratitude to Dr. Theresa Zammit Lupi, Head of Conservation at the University of Graz, for allowing us to work on this project at her private conservation workshop in Rabat, Malta.

Further reading

Scheper, Karin. The Technique of Islamic Bookbinding: Methods, Materials and Regional Varieties. Second Revised Edition. Islamic Manuscripts and Books 8. Leiden; Boston (MA): Brill, 2018.

David Plummer was born and raised in the Welsh Marches. He is currently employed by the Archdiocese of Malta as a conservator and is a Fellow of the Royal Asiatic Society.