It is often said that a bad craftsman blames his tools, but it is also true that a good craftsman with the right tools will do good work. All too often, newly graduated conservators find themselves in practical work and realise that their tools aren’t quite cut out for the task, as certainly was the case for us when working with leather. Our knives never seemed to stay sharp, and jobs that should have been straightforward tasks became obstacles of frustration. This May, we were lucky enough to participate on a three-day course in knife making and sharpening, jointly organised by the Oxford Conservation Consortium (OCC) and Bodleian Libraries Conservation. The course was led by Bernard Allen, a designer-craftsman with 20 years of experience teaching sharpening to conservators.

The course focused on the central goal of shaping and sharpening a new English-style edge paring knife and a number of small precision lifting knives. Through the process of grinding, shaping, flattening and sharpening we discussed the physics of a sharp edge and the importance of hardened steel for maintaining an edge. Bernard had sourced Niolox metal for our paring knives, a stainless steel alloy with good edge-retention and corrosion-resistance properties. For the lifting knives, we used hacksaw blades made of hardened steel.

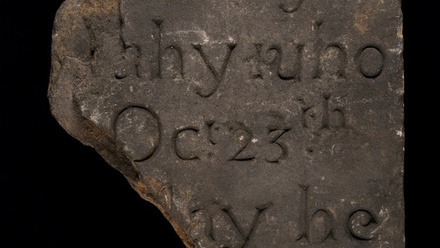

We began with the edge paring knife blades cut with a rough bevel, which required a considerable amount of work to shape and sharpen them precisely. The first stage was to ‘lap’ the back – to make it as flat as possible all along the edge of the blade. For this we used Japanese water stones, from a 1000 to 10,000 grit. We learnt to keep our sharpening stones flat using a diamond flattener, and to avoid rocking the blade in order to keep the surface as flat as possible. One small mistake can cost hours of sharpening.

Next, we shaped the bevel using the Tormek T-8 sharpening machine. This consists of an aluminium oxide grinding stone that sits in a trough of water. When switched on, the stone turns through the water, meaning that it is kept constantly cool and wet. The coolness is of utmost importance: it keeps the temperature of your blade low as you sharpen it, meaning that the steel does not lose its ‘temper’ and thus its hardness and ability to retain an edge. Tormek machines also allow you to attach various jigs which hold your blade in place, making it easier to maintain the same angle of bevel. Because of the size of our blades, we used a platform attachment. Pressing on the tip of the blade while moving it back and forth across the platform, perpendicular to the stone, we slowly shaped our bevels until we had a small burr along the edge of the knife.

Bernard warned us of what he called ‘burr fascination’—the urge to fiddle with the burr so much that it snaps off, which leaves you with a flat, blunt edge again! Instead he showed us the proper way to remove the burr on the water stones, placing the blade flat on the stone and drawing it backwards, then flushing away the small steel particles with water so that they wouldn’t get under the blade and scratch it. After that, it was on to sharpening the bevel. For this, we worked again through the water stones from 1000 to 10,000, only this time we had to be careful to keep the angle of the bevel correct as we went. It was also more important than ever that we didn’t rock the blade onto its edge, as this would undo all our hard work on the Tormek.

Once we were happy with our bevels, we did some fine-tuning on the backs of the blades and then we were done! Or so we thought… As Bernard also reminded us, steel benefits from ‘work hardening’ in which the metal’s structure is changed via stress to make it even harder. He therefore encouraged us to use our blades until they were blunt and then sharpen them up again, to get this process going.

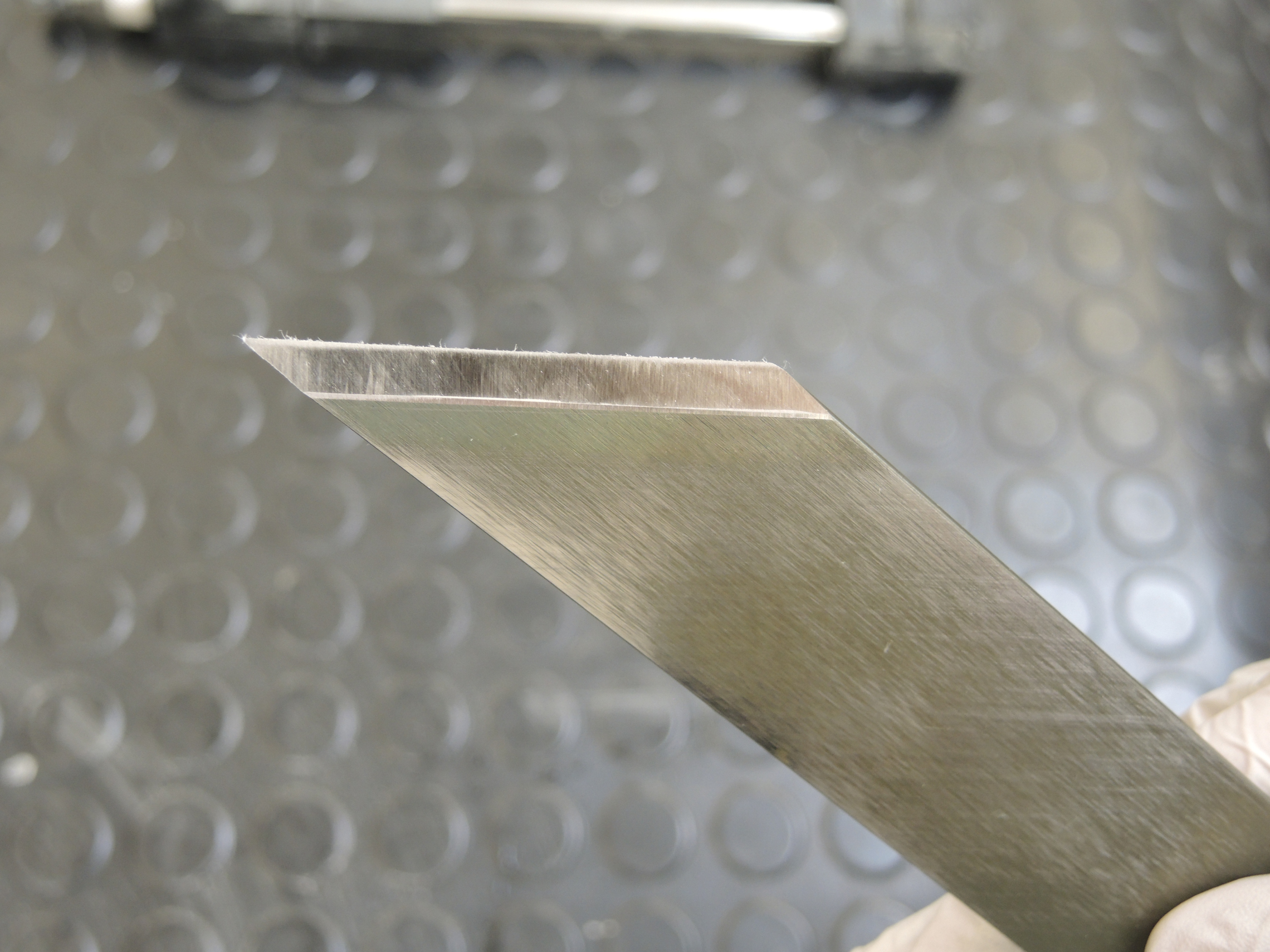

Bernard also instructed us in the use of a grinder, so that we could shape several lifting knives to our preferences. This was not a water-cooled machine like the Tormek, so we had to be careful not to overheat the metal. Luckily, it’s obvious when you’ve done this as the steel goes a different colour when its temper is lost, and you can then sneakily grind away that part to correct your mistake…! To complete the knives, we used the Tormek to shape the bevels as before, and a combination of diamond and water stones for lapping and sharpening.

![]()

OCC conservator Jasdip Dhillon shapes a lifting knife on the grinder.

That was not all we packed into the three days. We also learned how to adapt and sharpen spokeshave blades, how best to sharpen curved French paring knives (something Jess had been particularly nervous about!), and even how to keep our scissors sharp. The course was spectacularly informative and productive. It left us with a wealth of knowledge that has already hugely increased our confidence and ability to maintain our various edge tools. We are so grateful to Bernard for his patience and encouragement while sharing his hard-earned experience with us, and also hugely thankful to the ICON Book and Paper Group for the bursary that helped us attend this fantastic course.

Tired but happy at the close of the final day

Nikki Tomkins and Jess Hyslop are book and paper conservators at the Oxford Conservation Consortium. Nikki graduated from Camberwell College of Arts before joining the OCC in 2015, while Jess completed her MA at West Dean College in 2016. She was a project conservator for one year at the Staffordshire and Stoke-on-Trent Archive Service prior to joining the OCC in 2017.