I would unreservedly like to thank the Clothworker’s Foundation for their support over the past two years, as their generosity has allowed me to undertake my role as the video conservation and curatorial intern at the British Film Institute.

Over the past two years, I have trained at the BFI National Film Archive in Berkhamsted. At the BFI in Stephen Street, as a global pandemic took hold, I have continued work with my colleagues based at Stephen Street, shifting from hands-on conservation to working from home in the Curatorial department on cataloguing complex collections. In my first year, I worked under Peter Young (video conservation team leader) in the video unit and my second year under Patrick Russell (senior curator in non-fiction) and Dylan Cave (collections development manager).

Building skills in Archive technology

The British Film Institute is an enormous cultural institution. At the beginning of my placement, I could not comprehend the directions, tasks, and skills I would hone in multiple departments. Within weeks I was involved in building our first major project for Heritage 2022, building a facility to digitise 1-inch magnetic tapes. I worked on cabling and creating BNC connectors, training with my supervisors to connect the system, and adjusting the configuration settings to balance the chroma, video, and black levels.

Retracing the steps to creating a public collection

I will be discussing the progression of my work on the Video Nation collection. The concept of Video Nation emerged from the mass observation social research organization based at the University of Sussex. Their work ended in the 1960s, but subsequent interest in their work revived the project in 1981. As curiosity around this project piqued, a series of projects emerged influenced by this research.

Video Nation opening title screen

The exploration of mass observation on TV has provenance at the BFI. The BFI television unit was involved with a project that culminated in a book and documentary broadcast on Yorkshire television called "One Day in the Life of TV." A few years later, the Community Programme Unit at BBC 2 began working on Video Diaries and encouraged people to record and send in shorts of themselves. The project eventually became Video Nation, and 50 contributors were given Hi-8 cameras to film themselves over a year. Of the 10,000 tapes recorded for Video Nation, 1300 shorts were edited and shown on TV. The BFI currently holds a third of these rushes and complete programmes from the BBC.

Video Nation is a collection that required tackling on a philosophical level; what do these films reflect? What is their cultural significance? The collection also required technical work through digitisation and curatorial work by identifying the material on tape.

How is magnetic tape conserved?

There is a dynamic relationship between interventive and preventive, preservation and conservation of tape. The preventive aspect of the work focuses on ensuring that the tape's environment is sufficient to maintain conditions where the image on film is not damaged. However, the material (casing) and magnetic tape are secondary to preserving the moving image. As a result, conservation processes focus more on maintaining the machines that play the material and the magnetic tape condition carried within the object. We conservatively use the original playback devices to mitigate damage to video heads and rare machine components. Therefore, archives and even curators cannot view entire collections before digitisation due to time and technological constraints. It would not be time adequate nor resource considerate.

Exhibiting and making a case for the collection

Therefore, my first task was to exhibit the cultural case for digitising Video Nation. I looked through tapes trying to establish a few characters who best represent and embody the project—looking at selected tapes that reflect the intimacy of the relationship between self-shot and directed footage and the transformation in the programme's structure. I devised a spreadsheet that carried details of individual programmes from the collection.

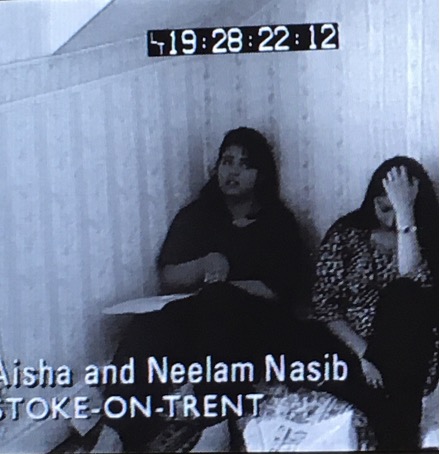

Assisted by curatorial archivist, Kristina Tarasova we selected a range of clips that reflected the series' subjects and topics’ diversity. I chose clips to reflect the changing nature of the series. Video Nation occurred in a world before the confessional culture of the internet and social media.

Over time authors and directors of their own lives became contributors; they became more comfortable with the camera and presented a serialized version of their lives. They began to stage their interactions more carefully. Discussions moved from intimate spaces like the bedroom to living rooms, dining rooms, and the garden. The series format went from shorts to compilations. We endeavoured to pick an earlier and relatively intimate episode recorded as a compilation; this reflects the midpoint of the show between the beginning: crudely filmed shorts that were very personal, to the end: seasoned contributors discussing a topic in an established format.

I picked clips to reflect this changing reality. There is a modern comparison that can be observed with a series like Gogglebox. Still, the concept of directing and crafting a broadcasted version of your life was unfamiliar at the time. I focused on subjects who appeared regularly and screened the original format, a compilation, and concentrated on ethnically, sexually, geographically, and age-diverse topics. Covering a range of themes from religion, multi-generational homes, race, and death, I selected videos that encapsulated the subjects' range.

These extracts were screened at the BFI Stephen Street to a small group of interested curators.

Still from Video Nation screening

Digitisation work

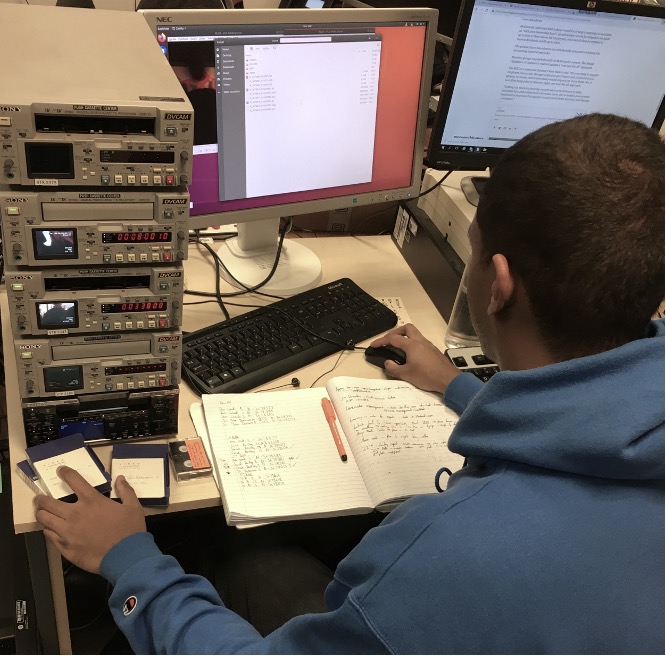

Video Nation was selected for Heritage 2022 and will be digitised in two stages. As part of the initial phase of digitisation, my work focused on a small selection of DVCam tapes and the Hi-8 tapes that the participants used to film themselves.

Hi-8 and DvCam tapes are two later tape formats and antecedent of initial formats. They are comparatively small and relatively young videotape formats only introduced fairly recently in the 1990s. DvCam is a ¼” tape, and Hi-8 is an 8mm tape format. Hi-8 tapes are somewhat fragile.

Xavier digitising Hi-8 and DvCam tapes

The Hi-8 and DvCam tapes are played back through their respective tape players concurrently. Using capture software, as the tapes the tape play, they are converted to a digital file. As these files playback, I monitored the progression of the recordings. The Hi-8 videos were about 15-20 years old at the point of digitisation. The format's fragility presented issues within the material’s playback, leading to frequent dropouts across particular tapes. In other formats, there are means to remedy this through interventive treatments on 1-inch and 2-inch. We use cleaning machines to prevent the coagulation of desiccated ferric oxide on the surface of the tape. To remove the humidity in the body of 2-inch tapes, we can bake them.

Example of dropout on a Hi-8 tape

The problematic Hi-8 tape had issues with progressive binder failure and demagnetisation; this can be observed through on-screen faults. These issues were not extensive enough to merit an increased focus on interventive treatments. Receiving the best results can at times be an imprecise science, but after cleaning the tape with compressed air on playback, we managed to obtain an improved recording.

Upon completion, this was the first step towards the larger digitisation project that awaits, the more significant part of the collection of Betacam tapes for Heritage 2022.

Conclusion

Getting to work across two departments has been an incredible opportunity. The skills I learnt within my first year of my placement informed my second year of remote working with the Curatorial department throughout the pandemic.

Overall this experience has shaped my career and provided me with experience working on specialist collections. I want to thank Shulla Jaques ACR and Patrick Whife from Icon, Peter Young, Alex Zorba, Patrick Russell, Vicki Kelsall, and Dylan Cave from the BFI for shaping and managing this internship throughout a historically tricky period.

Lead image: Video Nation opening title screen, © BFI