Introduction

Apart from engagement with routine collections care activities including environmental monitoring and control, integrated pest management and housekeeping, I am appraising and reviewing the monitoring and management of light in the Museum.

Coupled with data gathering, I am auditing current practices, identifying risks, and devising potential mitigation measures through consultation of academic research and benchmarking against other institutions. The aim is to generate a consultation report, culminating in draft policy and procedural documents.

As Covid-19 has forced many of us to work from home, it has become more apparent than ever that digital and technological competence is increasingly indispensable. From video conferencing to basic coding skills or ways to fix a broken computer, we are now facing new technologies which are part of our home and work life. Understanding them is essential.

Goldman-Sachs’ 2016 report The Low Carbon Economy claims that light emitting diodes (LEDs) are one of the quickest adoptions of new technology in human history and, with the shorter lifespans of older lamps, it is predicted that almost all lighting globally will shift wholly to LEDs in the 2020s (https://tinyurl.com/y9p4k8r3). To that end, this blog post will discuss recommendations related to selecting and managing new and existing light sources, ecspecially the increasingly ubiquitous LED.

Need for Policies and Procedures

Constant technological change in lighting requires museum professionals to stay abreast of new advances and remain aware of how changes may affect collections. As a response, in recent years, there have been many developments in the monitoring and management of light in museums.

Policies and procedural documents can vary between institutions and take different formats- with some institutions producing detailed, stand-alone light management documents, while others include a short synopsis of light monitoring practices within larger collection care plans. Differences are based on institutional expertise, staff time, funding, building constraints, and individual collection requirements.

Despite the variety of formats, organisational policies and procedures are beneficial in promoting uniform actions over the long term despite potential alterations in staff, funding, or equipment. Utilising policies and procedures:

- Ensures compliance with sector standards and/or legal requirements

- Supports improved, streamlined decision-making, generating parameters for actions

- Promotes better, more uniform, and time-conscious actions, and

- Encourages staff awareness, decreasing siloed decision-making

However, I have found generating successful policy and procedural documents can be challenging, especially regarding light monitoring and management, and can easily fall prey to being overly prescriptive and inflexible. Excessively cautious object exposure periods or light levels could lead to tension between conservators and exhibition staff and reduce visitor access to collections (Colby 1992). Similarly, policies and procedures need to manage uncertainty- knowing the light exposure history of objects or the chemical composition of all objects within a museum, may not be possible or feasible (Ashley-Smith et al 1994, Henderson 2017).

Policies need to promote accessibility and be clear, evidence-based, simple to follow and linked with the other museum procedures (Saunders 2020).

Traditional Light sources

There are many light sources available to museums, but recent legal changes are making some light sources obsolescent.

Incandescent light sources - including tungsten and tungsten halogen lamps - are electric light bulbs with a wire filament (unsurprisingly, usually composed of tungsten) which is heated until it glows. The addition of a halogen gas reduces darkening of the bulb.

In 2007, the UK government announced that traditional tungsten bulbs would be phased out by 2011, with tungsten halogen, as stated in EU directives, being phased out from 2023 onwards (https://tinyurl.com/y7ehfluo). Due to their long life, many are still utilised in museums, and the Fitzwilliam Museum is no exception.

Fluorescent lamps emit light by ionising mercury vapour within the glass tube or bulb. This causes electrons in the gas to emit photons at ultraviolet wavelengths. Ultraviolet radiation is converted to white light by phosphors within the glass cylinder. A phosphor is a material which emits luminescence when excited by light.

Similar to tungsten halogen bulbs, fluorescent tubes are being phased out from 2023 onwards and are still in use at the Museum.

What are LEDs?

A light-emitting diode or LED is a semiconductor light source which emits light when a current is passed through it. White LEDs can be generated using four different methods, but the most widely used approach uses a blue-light chip coupled with a yellow phosphor. In this type of LED, an amount of short-wave blue light produced by the semiconductor excites the phosphor which emits yellow light. White light is generated by the mixture of phosphor generated yellow light with non-absorbed, residual blue light, which we perceive as white light.

LEDs are being widely introduced within museums as they:

- Are energy efficient - LEDs have a high luminous efficacy (which is a measure of how well a light source produces visible light)

- Have a long life, which means reduced maintenance requirements

- Are cost effective

- Have a higher quality light output. This can be measured by colour rendering index (CRI) which records the ability of light to render colours.

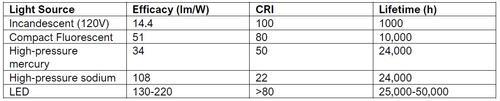

Below is a table which highlights why LED lights are becoming commonplace. From a collections care perspective, legacy light sources can emit higher quantities of ultraviolet and infrared radiation which can damage objects.

Challenges at the Fitzwilliam Museum

Light is an essential component in our ability to view, understand and interpret museum collections, but can also lead to the deterioration of certain materials. Every museum will have its own, unique challenges to face when enacting light management and monitoring practices.

First opened to the public in 1848, and with several 19th to 21st century extensions, the Fitzwilliam Museum holds a diverse and internationally important collection of fine and applied art, antiquities, coins and medals and manuscripts and printed books. [1] This great variety of objects, from different cultures and time periods, is composed of a wide range of materials - all with varying sensitivities to light.

At the Fitzwilliam, lighting practices and procedures need to consider the architectural character and Grade 1 Listing [2] of most of the different parts of the building. The older parts were designed to be illuminated principally by natural light which is more challenging to control than artificial sources. In addition, the variety of objects and materials on display is vast and the management of the different departmental collections complex. As with other museums, resources are limited and rotation of collections (while an option) is not always sustainable.

Current Practice

Light management and monitoring procedures are integrated within the Museum’s Collection Care Plan document. Like other institutions, the Fitzwilliam Museum is not bulk-replacing old lamps because disposing of and replacing old technology is not cost-effective or environmentally friendly. Older light systems are being replaced by LED systems on a case by case basis, mostly as part of both repair and refurbishment projects of individual galleries. In these cases, a lighting designer may be brought in as part of the project and a complete system created for that space, but with the expectation that the control mechanism can be linked into the existing network.

One challenge is the development of a strategy that encompasses these types of development and the on-going gradual replacement of older light sources across the institution with LEDs. At the moment, these two schemes run parallel to each other.

The Fitzwilliam Museum is committed to controlling and reducing, as feasibly as possible, overall light exposure to light sensitive objects. Galleries and rooms in which collections are studied, conserved, and mounted are mostly lit by a combination of natural and electric light. To control natural light, roof lights and windows are covered with MT20 UV3 and light reducing film or simple UV filtering film where the listing does not permit the mirror finish MT20. The effectiveness of the films is checked quarterly with a schedule of replacement. [3].

Most windows and roof lights are also shaded by other means (fabric blinds, louvre blinds, translucent glass) and, out of public opening hours, ground floor windows are covered by steel shutters which exclude natural light.

Control of electric lights is carried out partly through a programmable Dynalite control system (and new DALI system in selected areas) and partly through manual management to ensure minimal exposure of the collections. Where UV radiation is emitted from artificial light sources, it is excluded by filtration.

In areas where light is not monitored by the telemetric environmental monitoring system, lux and ultraviolet spot-readings are taken intensively for one week in each quarter and recorded for interpretation and consultation.

Proposed Outcomes for the Project

Using an Elsec combined light and ultraviolet meter and Spectis spectral light meter, I have been collecting light data including illuminance (lux), ultraviolet radiation (mW/cm2) and spectral power distribution (SPD), from walls of gallery spaces and from display objects understood to be vulnerable to light damage .

The SPD is the normalised power per wavelength interval throughout the spectrum. Importantly, the spectral light meter can assist in clarifying if short wavelength visible light (which can be harmful to some pigments) and infrared radiation (IR) (which can cause localised heating on some object surfaces) are present. Gathering SPD data could also be helpful at determining problems or degradation of LED or other light sources.

This data has allowed us to see the local lighting environment for objects. This information will be fed into the Museum collections management software and, on an object by object basis, will serve as a starting point from which we can build up knowledge of the current light exposure of objects on display along with remaining aware of any issues with bulbs [4].

Using previous light monitoring and annual modelling data which the Museum has undertaken, I will be able to get an idea of the lighting environment and problematic areas within gallery spaces. Using a gridded division of rooms and cases and additional location documentation, I am looking at devising nomenclature which can be added to the Museum collections management software which will allow individuals to see the lighting conditions of areas and, using a procedural vulnerability matrix, whether the material is suitable for display or whether a risk management strategy (rotation, increasing the frequency of conditions checks) is required.

Data collection and interpretation are ongoing as the Museum is currently closed but will continue when staff are able to enter the building again.

Conclusion

Developing useable procedures can sometimes be challenging in collections care and having simple and useable guidelines which coalesce recent research and technological change can be difficult. I have thus far found the internship at the Fitzwilliam Museum a fascinating, intellectually challenging and rewarding experience. I have enjoyed devising ways to distil complex scientific and technological data into useable real-life procedures.

Gathering detailed information about the lighting environment within the Museum and developing a more nuanced approach to monitoring light and determining exposure periods and risk has been interesting and I am looking forward to getting back into the Museum and continuing to delve into the project further.

LEDs are quickly replacing legacy lamps in museums. The Fitzwilliam Museum, along with the rest of the sector, needs to prepare. Lighting policies and procedures are beneficial at creating uniformity over the long term, despite changes in staff, funding, or equipment.

As technology is rapidly changing and (arguably) improving the world around us, it is important that collections care conservators embrace that change, being proactive and not simply reactive to new technologies.

---

Bibliography

Ashley-Smith, J., Umney, N. and Ford, D. 1994. ‘Let’s be honest- realistic environmental parameters for loaned object,’ Studies in Conservation, vol. 39, iss. Sup. 2: Preprints of the Contributions to the Otawa Congress, 12-16 Sept. 1994. Preventive Conservation: Practice, Theory and Research.

Colby, K. 1992. ‘A Suggested Exhibition Policy for Works of Art on Paper,’ Journal of the Institute for Conservation, Canadian Group, vol. 17, no. 3.

Henderson, J. 2017. ‘Managing Uncertainty for Preventive Conservation,’ Studies in Conservation, vol. 63, iss. Sup. 1: IIC 2018 Turin Congress Preprints.

Saunders, D. 2020. Museum Lighting: A guide to Conservators and Curators. Los Angeles: Getty Institute.

Van Driel, W.D. and Fan, X.J. 2012. Solid State Lighting Reliability: Components to Systems (Chapter 2). New York (NY): Spring – Verlag.

Yazdan Mehr, M., Bahrami, A., van driel, W.D., Fan, X.J., Davis, J.L. and Zhang, G.Q. 2020. ‘Degradation of Optical Materials in Solid- State Lighting Systems,’ International Materials Reviews, vol. 62, iss. 2.

Footnotes

[1] Read more about the amazing collection at the Fitzwilliam Museum here- https://www.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/

[2] A listed building is a structure of historical significance which cannot be altered, dismantled, or extended without consultation of the local planning authority (LPA) and, typically, the relevant government agency. In England, the government agency is Historic England- https://tinyurl.com/yabgznxz

[3] MT20 UV and visible light reduction window film, developed by Sun-X, reduces incident UV radiation and part of the visible spectrum within a gallery space- https://tinyurl.com/y9vvhzz4

[4] As LEDs have a 17+ year lifespan, monitoring incident radiation, such as recording spectral power distribution data over the long term, may be beneficial in ensuring the Museum is cognisant of any sources of degradation within the luminaire, safeguarding that the Museum is aware of when to purchase replacements and that any collection care concerns caused by equipment degradation are actively dealt with.

---

Images: Ian Channell