One of my early projects was the treatment and examination of a collection of Dutch and Flemish drawings which included works by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Rubens and van Dyke. The drawings had been identified as requiring treatment after a collection survey highlighted the use of cellulose acetate windows within their mounts. Once considered a stable material, cellulose acetate is now known to degrade relatively rapidly, via hydrolysis, causing the release of damaging acidic products. Furthermore, the windows were sometimes affixed to the mounts using pressure sensitive tapes. Upon aging, these tapes can embrittle and yellow, with the potential to cause irreversible staining and damage to paper objects.

Project Aims

The primary aim of the project was to lift, repair and re-mount the drawings in new mounts made of conservation grade materials.

During the project I learnt new practical skills such as undercutting; a method used to remove works which have been edged in (directly adhered on all four edges) to their mounts.

An agarose gel strip is used to remove methyl cellulose poultice residues on the verso of J.A. Backer’s (attributed to) Head of an Old Woman, c.1623-1651, (P&D 1897,0813.9(95)).

I experimented with various adhesive and debris removal methods, including agarose and gellan gum gel application, both of which proved particularly effective at removing methyl cellulose poultice residues.

I was also able to practise my colour matching skills by toning infill papers.

In addition to improving my practical skills the project presented an opportunity to examine several of the drawings in detail and learn more about the materials and techniques commonly found in Old Master drawings. Under the instruction of Senior Conservator Jude Rayner and in conjunction with Conservator Rebecca Snow, I conducted an extensive visual examination of Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s Calumny of Apelles (c.1565-1569).

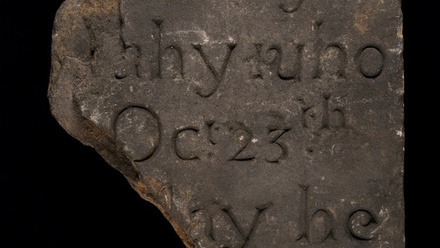

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Calumny of Apelles, c.1565-1569 (P&D 1959,0214.1) Characters, from left to right: Truth, Penitence/Repentance, Innocence (the child), Treachery/Guile, Deceit, Calumny/Slander, Envy, Suspicion, Ignorance, The King.

The drawing depicts an interpretation of a classical allegorical scene about vice and virtue, based upon the description of a famous lost painting by Apelles, a 4th century (B.C.) Greek painter. It is catalogued as “pen and ink on brown prepared paper” and, of the less than 70 known surviving Bruegel drawings (Sellink, 2013), this example is the only one to depict a classical scene.

Visual Examination

Examination began by looking at the image in ambient visible light. General observations regarding the support, media, technique and condition were made to act as comparisons with the results of the other visual examinations. After this the drawing was examined using transmitted light, followed by raking light and finally under varying magnification. Each time, overall observations were made before details were examined more closely.

Transmitted light

As the drawing was unlined, multiple historic damages and repairs were visible. These included numerous skinned areas to the edges and across the body of the image, indications of previous mounting and possible lining.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Calumny of Apelles, c.1565-1569 (P&D 1959,0214.1) photographed in transmitted light.

Physical information about the paper was also revealed. For example, it was possible to see that the chain lines had an irregular arrangement between 23 and 27 mm apart, with slight shadowing either side. Some of the lines had a wavy appearance, an interesting distinguishing feature which Jude suggested could be evidence of an old or damaged mould.

The laid lines measured approximately 8-10 p/cm and were also distinctive. They showed bands of thickened pulp, which appeared as shadowing, every 5-6 cm, perhaps evidence of a double-layered mould being used. Unfortunately, there was no watermark or countermark, and the sheet had obviously been trimmed, so it was not possible to gain any information regarding the paper’s origin. However, at this time Bruegel (c.1565-1569) was known to be working in Brussels and this information, along with the unique characteristics of the paper, could act as good starting points for further research.

Raking light

We next looked at the image using raking light. This confirmed that the recto was the wire side, as small linear depressions from the wires of the paper mould were noticeable in the lower left corner. The ‘toothier’ appearance and hair-like impressions on the verso confirmed it was the felt side.

Often raking light can reveal signs of artistic process such as blind stylus underdrawings, which were seen in the visual examination of the Rubens drawing (P&D 1858,0724.2), included in this project. However, none were found in the Bruegel drawing.

Peter Paul Rubens So Called Bust of Seneca c.1592-1640 (P&D 1858,0724.2) photographed in raking light. Blind stylus underdrawings are clearly seen in the beard, around the eyes and to the neck.

Magnification

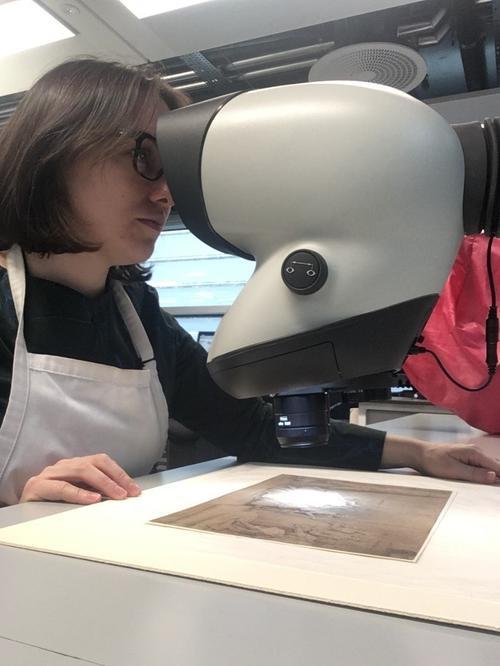

Finally, we moved on to looking at the drawing using two forms of magnification, firstly a Mantis stereo viewer and secondly a Lecia Stereo microscope. The Mantis provides x4 and x10 magnification and is particularly useful for examining artistic technique, whilst the Lecia Stereo microscope, with its higher-level magnification, is ideal for viewing media details such as pigment particles.

The Support

The paper appeared to be of high quality, having a uniform and even fibre structure and just the occasional blue-coloured or woody fibre embedded in the furnish. It was also possible to see some blue/grey coloured fibres to the surface of the verso, potential indicators of a previous lining.

Examining Bruegel’s Calumny of Apelles (P&D 1959,0214.1) using the Mantis stereo viewer.

The Media

When viewing the drawing in ambient light the ink lines all appeared to be of a similar warm brown tone. The tonal background areas, whilst different shades, also appeared to be similar, and likely one medium applied in varying dilutions.

When viewing the lines using the Mantis, around 4-5 different ink tones, applied in varying dilutions were observed. Whilst the Lecia revealed that the majority of the lines were not brown in colour, rather they have a grey hue, with a slight lustre, and small grey-black coloured particulates could be seen embedded within the paper fibres. This information suggested that a carbon-based ink was used for the majority of the delineated areas.

When viewing the tonal background and foreground areas under magnification the media in these areas had a slight lustre, appeared smooth, uniform and sunk into the paper fibres, with some lower areas of the paper structure appearing untoned. This is suggestive of a thin and flowing liquid media being applied lightly. The slight lustre and the similarity in tone to the ink lines would indicate that the same, or similar medium was used across the composition.

However, some of the ink lines had a different appearance. For example, the lines on Calumny’s skirt, the detailing on the tunic of Innocence, additions to the face of Ignorance and to the damage in the centre of the drawing around the hands of Calumny. These areas had a more reddish/brown tone to them, appeared more opaque and crisper and, significantly, had a slightly crusty appearance; all of which are more typical of an iron gall ink. As such it is likely that both inks are present in the drawing.

Magnification was also useful for examining some of the more conspicuous areas where other media had been applied. For example, several damaged areas appeared to have been re-touched using a dry, rich brown coloured medium, possibly chalk or pastel. The visual similarity of the media in these areas suggested that they were likely treated at the same time.

When viewing the somewhat incongruous white-coloured highlights to the faces of Calumny and Suspicion using the Lecia microscope, it was clear that a thick paint, probably body-colour, had been applied with a brush. On the face of Calumny there were also some yellow/ochre coloured particles indicating the application of another pigment at some point. Although the method of application is apparent the reasoning for it is not. Perhaps the white was being used to conceal damage or compositional alterations beneath or is an indication of the unfinished nature of the drawing.

Technique

Upon close inspection the delicate and detailed nature of the drawing was particularly evident. From the diminutive brush strokes on the walls, creating the appearance of cracks, to the most minimal of lines expertly used to craft the highly expressive faces. Each line seemingly precisely placed to emphasise both the drama and humour of the narrative. With such a detailed drawing it would seem plausible that a sketch, prior to the ink application, would have been done. However, no convincing evidence for underdrawings was observed.

Despite this, however, it was still possible to draw-out some information regarding the execution of the image. Some lines appeared sharp and crisp, akin to pen application, whilst others had a soft fluidity to them, more suggestive of brush use. Furthermore, some light-coloured areas around the shoulder of Envy and the peak of Treachery’s skirt appeared to be regions of natural untoned paper. Although difficult to discern with complete certainty, this seemed to suggest that the paper may not have had an overall preparatory wash applied to it, but that instead the line drawing was made first and the background wash applied second. Not only does this indicate a highly accomplished hand, it also reveals more about Bruegel’s working procedure and it would be interesting to see if this working practice could be observed in other Bruegel drawings.

Reflections

After completing my examination of the Bruegel drawing, I compiled my findings into a formal document and in doing so I was able to reflect upon what I covered during the project as a whole. I had learnt new practical skills, improved my decision-making abilities and increased my self-confidence, especially through deciding on and implementing debris and adhesive removal methods. Systematic examination using only visual methods improved not only my observation skills but increased my material knowledge. And I certainly feel more confident in my ability to recognise the appearance of different types of media. A personal goal during my internship was to increase my understanding and knowledge of artistic media and artwork construction and through this project I was undoubtedly able to work towards this ambition. My material knowledge has most definitely improved, as has my understanding of the complexity of Old Master drawings. All aspects that I can continue to build upon, not only as my internship progresses but also as my career develops.

Thanks

Firstly, I would like to thank the Clare Hampson Fund for their generous support of this Icon Internship, whose financial support has made this opportunity possible. I would also like to thank Icon and my Icon Intern Advisor Shulla Jaques ACR for their guidance and support, my supervisor Caroline Barry ACR for providing fantastic training and wonderful opportunities, to Jude Raynor ACR for her excellent teaching in technical examination, Rebecca Snow for her patience and ability to answer all my questions and to all members of The British Museum Pictorial Art section who have made me feel so welcome and part of lovely team.

Reference

Sellink, M. (2013) “The Dating of Pieter Bruegel’s Landscape Drawings Reconsidered and a New Discovery”, Master Drawings 51(3), pp.291-322.